Page updated:

May 4, 2021

Author: Curtis Mobley

View PDF

The Quasi-Single-Scattering Approximation

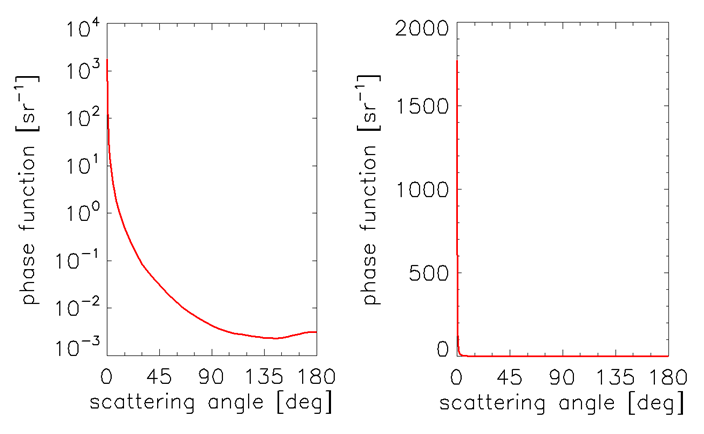

For highly peaked phase functions such as those typical of ocean waters, most of the scattering is at very small scattering angles . For some purposes, scattering through a small scattering angle is almost the same as no scattering at all. The quasi-single-scattering approximation (QSSA) exploits this observation by assuming that the forward-scattering part of the phase function can be represented by a Dirac delta function at scattering angle , with no scattering at all for . At first glance this seems like a terribly inaccurate approximation of reality for phase functions like the Petzold “average-particle” phase function) shown in the left panel of Fig. 1 . However, when plotted on linear axes as in the right panel of the figure, the approximation looks more reasonable. In practice, it can yield surprisingly accurate results for quantities that depend mostly on absorption and/or backscatter (such as and ).

The QSSA can be traced back to Hansen (1971), who used it in studies of reflection by planetary atmospheres. Gordon (1973) introduced it to oceanography for ocean color remote sensing of the ocean.

The QSSA uses the formulas of the SSA, but treats forward scattering as no scattering at all. With this approximation, the beam attenuation coefficient becomes

With this approximation for , the single scattering albedo and the optical depth become

and

where is the backscatter fraction. The QSSA thus replaces , and with *, and respectively. This is an example of a similarity transformation in which the solution of one problem is rescaled to obtain the solution to a different problem.

The QSSA was developed for reflectance calculations, so let us compute the QSSA approximation for the remote-sensing reflectance . The SSA solution for ,

| (1) |

with the approximations of the QSSA becomes

When evaluated just below the sea surface at , this quantity is related to by

| (2) |

Here t is the transmittance of radiance from water to air. For nadir-viewing radiance, and . is the index of refraction of water, and the ratio of irradiances (close to 1 for solar zenith angles away from the horizon) converts the underwater irradiance to the above-water value used in the definition of . Thus for nadir-viewing we have

| (3) |

The factor of is determined by the shape of the total phase function, which in turn is determined by the type of particles in the ocean. The factor is determined by solar angle. The remaining factor,

shows that, to first order, depends on the IOPs via , where both and are functions of depth and wavelength. is sometimes called the Gordon parameter in recognition of his use of this quantity in numerous ocean remote-sensing studies.

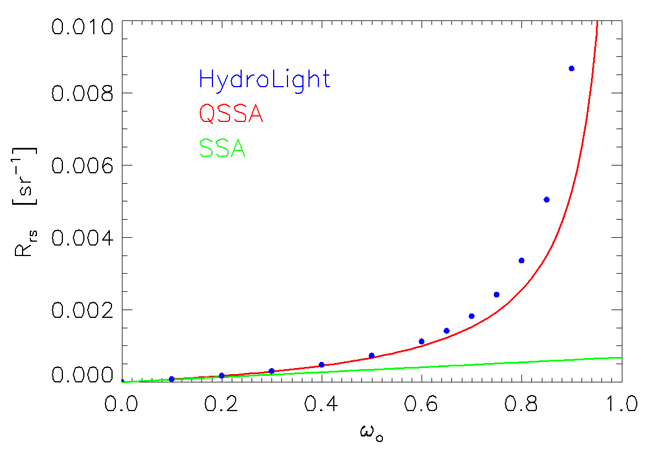

Figure 2 compares the accuracy of the QSSA as a function of with the SSA and with HydroLight computations that include all orders of multiple scattering. The HydroLight run used the Petzold phase function of Fig. ??, for which the backscatter fraction is . The sun was placed at 30 deg in a black sky, and the sea surface was level. This figure shows that the SSA does well only for . The SSA is almost a factor of four too small at , whereas the QSSA is only 16% too small. Even at the QSSA is only 35% too small, whereas the SSA is only one tenth of the correct value.

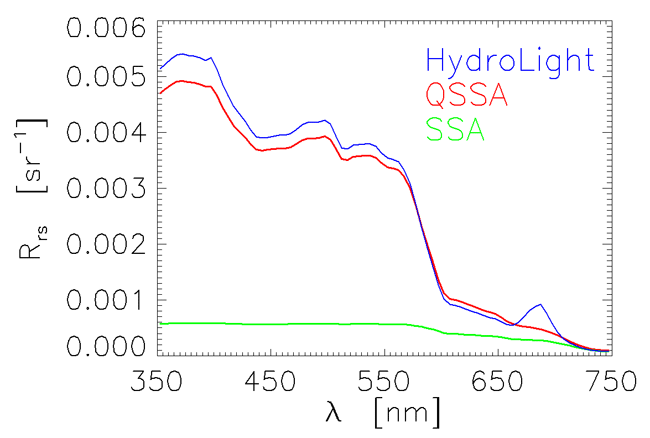

The blue curve of Fig. 3 shows an spectrum computed by HydroLight for homogeneous Case 1 water with a chlorophyll concentration of . The phytoplankton were modeled with a Petzold average particle phase function as used above. The sun was at 30 deg in a clear sky, and the wind was . Those sky and surface conditions violate the assumptions of collimated incident radiance and a level sea surface that underlie the SSA and QSSA. Nevertheless, the QSSA, evaluated using the IOPs generated by the HydroLight bio-optical model, gives an amazingly close prediction of the exact spectrum even though was in the range of 0.80 to 0.86 between 350 and 575 nm. The QSSA of course does not capture the chlorophyll fluorescence peak near 685 nm. The SSA fails badly until near 750 nm, where is less than 0.15.

The excellent performance of the QSSA seems counterintuitive given the crudeness of its phase function approximation. Why, in particular, does it do better than the SSA, since the SSA uses the full phase function, which is certainly a better description of nature than a delta function for forward scattering? The answer lies in how backscattering is parameterized in the QSSA. Note from Eq. (1) that in the SSA the backscatter part of the phase function is weighted by (multiplied by) . For a typical water body with a scattering coefficient four times the absorption coefficient, , and a Petzold phase function with a backscatter fraction of , this gives

Equation (3) shows that the QSSA for the same water weights by

Thus, for these IOPs, the QSSA weights the backscatter part of the phase function by a factor 4.66 times greater than that of the SSA. This corresponds precisely to the increase in for the QSSA compared to the SSA as seen in Fig. 2 for . In effect, the QSSA accounts for the “missing” multiple scattering in the single-scattering formulation by increasing the amount of backscattering. In other words, the QSSA parameterizes multiple scattering within the single-scattering mathematical framework by artificially increasing the backscattering.

The main utility of the SSA and QSSA is in the insight they give to the dependence of various AOPs on the IOPs. We saw above that depends primarily on . Likewise, the SSA and QSSA both show that near the sea surface depends primarily on . Gordon (1994) shows comparisons between the SSA, QSSA, and numerical (Monte Carlo) computations of other quantities such as the near-surface irradiance reflectance and .

Two more comments must be made for completeness. As Gordon noted in his original paper, the desired partitioning of scattered radiance is into upward vs. downward components. His development and the one above truncated the phase function out to a scattering of deg. This separation of backward and forward scattering corresponds to radiance scattered into upwelling and downwelling directions, respectively, only if the sun is at the zenith. If the sun is not at the zenith, then the phase function used in the QSSA should include only the angles that contribute to upward scattering, in which case B in Eq. (3) is not exactly the backscatter fraction of the original phase function. However, as we have seen in the example calculations with the sun at a 30 deg zenith angle, the QSSA still works well for non-zenith solar angles even when evaluated with B equal to the phase function backscatter fraction. Finally, note that in the limit of no scattering, i.e., , the QSSA reduces to the SSA.

See comments posted for this page and leave your own.

See comments posted for this page and leave your own.